|

|

.gif) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

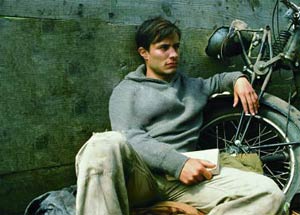

Based on Che Guevara's early days, The Motorcycle Diaries is a tender tribute to the young man, not the myth

Sunday, Aug. 22, 2004 As icons of the 1960s go, few are more ubiquitous and less understood than Che Guevara. His name has become a catch-all phrase for rebellion, and his image is on posters, mugs and boxer shorts, but only as the instantly recognizable two-tone portrait taken by Alberto Korda in 1960. In his evolution from Castro's right-hand man to the face that launched a thousand T shirts, Guevara has been frozen in time, always and forever the revolutionary. But most people have little sense of how he got there, or that, once upon a time, he was just a guy whose biggest problem was trying to get his girlfriend to sleep with him. Enter Walter Salles. In his latest film, The Motorcycle Diaries, the Oscar-nominated Brazilian director (Central Station) looks at Guevara before he started making history (imagine Mel Gibson making a film about a carpenter who wonders why he doesn't look like his dad). Salles' yet-to-be hero is the 23-year-old Ernesto Guevara, a romantic, asthmatic Argentinian medical student who hasn't yet picked up a gun or earned the nickname Che (a casual Argentinian slang word, like "O.K." or "buddy"). Part road movie, part coming-of-age story, the film is based on the journals that Guevara and his friend Alberto Granado kept on their eight-month journey across Latin America in 1952, from Buenos Aires through Argentina, Chile, Peru and Venezuela. The motorcycle of the title, a beat-up 1939 Norton 500 optimistically named the Mighty One, only makes it as far as Los Angeles, Chile, but stubbornness and curiosity keep the adventurers moving toward their destination: a leper colony in San Pablo where they have volunteered to work. On the way, they discover a uniting Latin American identity and witness the poverty, illness and social injustice a world away from their comfortable, middle-class lives. By the time they reach San Pablo, Guevara's consciousness has been raised, the seeds of revolution planted. "It's a film about the necessity to react to what seems unfair and unjust," says Salles, "about making choices that will have an impact not only on your life, but also the lives of other people." It was producer Michael Nozik, working with Robert Redford, who approached Salles with the idea of realizing Guevara's writings. "I had seen Central Station and knew I wanted to work with him," Nozik says. "Walter is the kind of director who's open to everything around him. He just goes with the flow and I think that adds to the vitality of the movie." To get hold of the rights, they went to Gianni Minà, an Italian journalist and documentarian who had received permission from Guevara's widow, Aleida March, to publish her late husband's manuscripts and turn them into a film. "I worked on it for seven years," Minà says. "But eventually I realized it would be impossible for me to make this movie. It would be too difficult to travel across Latin America with a crew of 50 people. It's difficult now with jeeps and helicopters, I don't

Mexican golden boy Gael García Bernal was Salles' first and only choice to play Guevara. "Could it be anybody else?" he asks. "Gael is the most visceral, talented and mature actor of his generation." Others have played the revolutionary onscreen: Omar Sharif in a much-reviled 1969 biopic; Antonio Banderas alongside Madonna's Eva Perón in Evita; and, soon, Benicio Del Toro in Steven Soderbergh's upcoming Che. They all look the part and get to gaze intensely, speak rousingly, and wave a gun — all film-friendly signals of impassioned freedom fighting. But the pre-revolutionary Motorcycle Diaries calls for naïveté, not intensity, and slowly dawning certainty instead of fervent resolution. Bernal isn't the hunky, smoldering Che; he's the thoughtful, awkward Ernesto — and he's splendid, though he doesn't radiate a potent sensuality the way he did as a scheming transvestite in Pedro Almodóvar's Bad Education. Instead, his Guevara is all goofy charm and dissolving innocence (more like his character in 2001's Y Tu Mamá También, but without the sex). His weapon is his wide, crooked smile. It's disarming and endearing, and as Guevara's carefree escapade turns into something far more significant, it proves an excellent tension-breaker. As his spirited friend and travel companion Granado, Rodrigo de la Serna (who's related to the real Guevara) provides the perfect foil to his shy, noble cohort. Guevara may be the heart of the film, but Granado — warm, witty and full of life — is its soul. De la Serna tackles the role of skirt-chasing, wise-cracking Granado with mischievous glee. And why shouldn't he? This is, after all, his story, too. In the great tradition of buddy movies, Guevara and Granado spend as much time arguing as they do hugging, and it's a joy to watch. No doubt it's their kinetic relationship — a little Easy Rider, a touch Butch and Sundance — as much as the stunning scenery (Machu Picchu, the Andes, the Amazon) and the sociopolitical undercurrent that made The Motorcycle Diaries a hit at Sundance and Cannes and has insiders whispering about an Oscar nomination. The film has already made almost $5 million in Brazil, Italy and Argentina (not bad for a film that cost less than $10 million to make), and as it opens in Britain this week it looks to be one of those rare cinematic creatures: a non-English-language film with real crossover appeal. "This part of Guevara's life is the most universally accessible," says Nozik. "Especially for young people, it taps into the questions of what you do when you're in school, or when you leave college, what do you do with your life? There is a sense of adventure there." It helps that the film never resorts to tub thumping. Salles doesn't explicitly lay blame for the social conditions they come across; instead he fills the screen with the real people that his actors, retracing Guevara's and Granado's steps, met and spoke with: dispossessed farmers, poor miners, homeless families and lepers. The stark black-and-white portraits show a population strong with pride. For just a moment, they become the icons. By peering behind the myth, Salles has made a man out of Che Guevara. The only glimpse of where the man is headed comes when Granado thinks aloud about the options for peaceful revolution. "A revolution without guns?" Guevara says. "It'll never work." That he would go on to help lead the Cuban revolution, be killed in Bolivia and become one of the most influential communist figures of all time is left for a blurb at the end. The Motorcycle Diaries isn't about greatness — it's about the potential for greatness. And this magical film is a far higher tribute than any T shirt.

From the Aug. 25, 2004 issue of TIME Europe magazine |

|||||||||||||||||

|